Juan's RLAC Notes

This written response is the result of an exploration of a corpus of South Asian colonial literature (by Amardeep Singh) using the corpus analysis tool AntConc. It is also a reflection on the ideas of nation, race, and caste of two authors on opposite sides of the Indian colonial ethnic spectrum. It is also, if the reader allows a bit of speculation and overinduction, a glimpse at the different thematic possibilities available from the same land to people of separate contexts.

Out of the numerous authors contained in the corpus, I thought it would be a good idea to contrast the most common topics and choices of authors on both sides of the colonial divide: the coloniser and the colonised. Because of their relative prominence, I chose to contrast Rabindranath Tagore and Rudyard Kipling in order to explore the relationship between the context of the authors and the way they describe the composition of society and their characters’ roles in it.

Kipling (left) and Tagore (right)

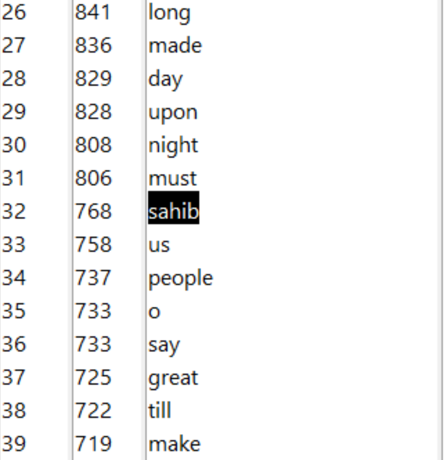

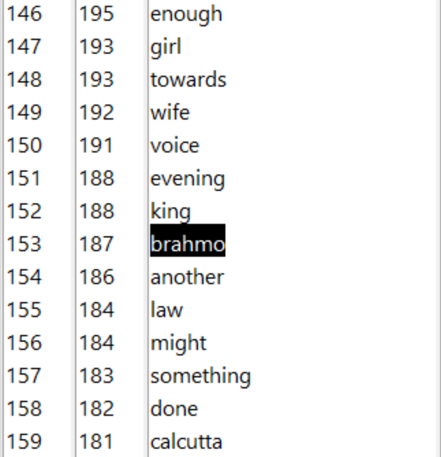

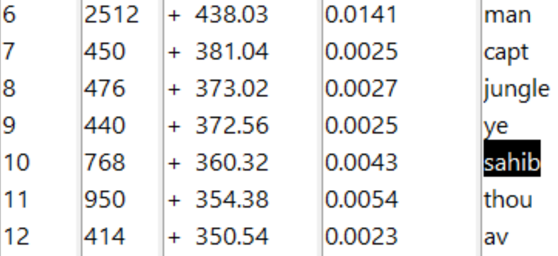

My first stop in this analysis was AntConc’s word list tool. I used this stoplist from NLTK to filter most function words. The first uncommon words to appear in the top of the wordlist (aside from the names of the main characters) are in both authors the titles with which the characters are addressed. In the case of Kipling, this is the word “sahib”, a word used in colonial India to address high-ranking English officials or landowners, while in the case of Tagore it is “brahmo”, the title given to the members of Tagore’s Hindu sect, or “babu”, a title for elders.

Word count rankings for "sahib" and "brahmo".

The prominence of Sahibs and Brahmos can be confirmed by using AntConc’s Keyword List tool, which compares the word frequencies of a corpus to another reference corpus. For each of the two authors, I used the works of the other as reference corpus, enabling me to see the words frequently used by one author but not by the other.

Keyword rankings for "sahib" and "brahmo".

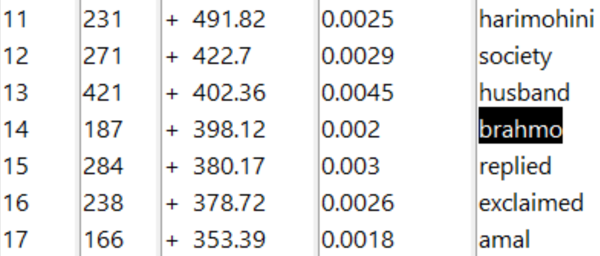

With this information, we can hypothesise that a good amount of the characters in both authors’ books are based on people of their ethnicity and social status. We can also look at the word clusters that contain “sahib” and “brahmo” and see that, in fact, we can obtain a list of main characters. We can also see, using these results and the Word List tool, what proportion of the main characters in both authors belong to these groups.

1. Binoy

2. Gora

3. Sucharita

5. Lolita

6. Paresh

8. Haran

9. Satish

Keyword rankings for (presumpt) Tagore main characters.

5. Binoy

6. Gora

15. Haran

21. Lolita

...

Characters collocated with "brahm*" (brahmo, brahmin, brahma...) in Kipling's works

We can transpose the top keywords of each author (usually the names of characters) with the top collocates for “sahib” and “brahmo” in order to do this. As it can be seen above, four of Tagore’s main characters appear associated with the title “brahmo”, a fact from which we can hypothesise that some of Tagore's main characters are from the same sector of society as him, or interact with people from it.

3. Kim

5. Tarvin

7. Mowgli

19. Lama

22. Kate

30. Colonel

43. Bagheera

Keyword rankings for (presumpt) Kipling main characters.

2. Tarvin

3. Lurgan

6. Petersen

8. Colonel

16. Yunkum

24. Creighton

35. Kim

Characters collocated with "sahib" in Kipling's works

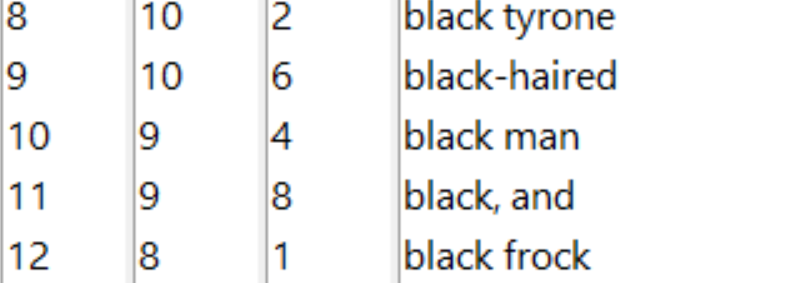

In the case of Kipling, although only two of the main characters are associated with the title of “sahib” (Tarvin and Kim), “sahib” is still collocated to many proper names of what could be supporting characters, which could mean that many of Kipling’s characters are based on other English people in India.

A deeper look at the keywords tool led me to find more words used to categorise people. This could give us an insight on how both authors think society is divided. To illustrate the differences between the two authors in regards to this, I also calculated the ratio of use of the words they use for these descriptions.

12. white

24. black

44. native

Keyword rankings for Kipling presumpt social descriptors.

is used 8.3x more frequently in Kipling

is used 7.6x

is used 70.9x

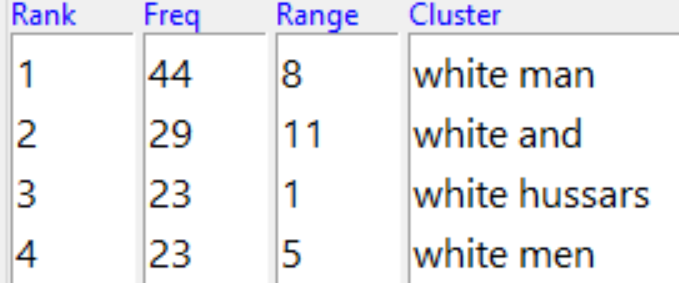

For example, the words “black” (#24), “white” (#12), and “native” (#44), according to AntConc’s keyword tool, are used way more frequently by Kipling than by Tagore, and are amongst the only top keywords that aren’t either names of characters or titles. We can hypothesise that skin colour is a defining feature of characters in Kipling.

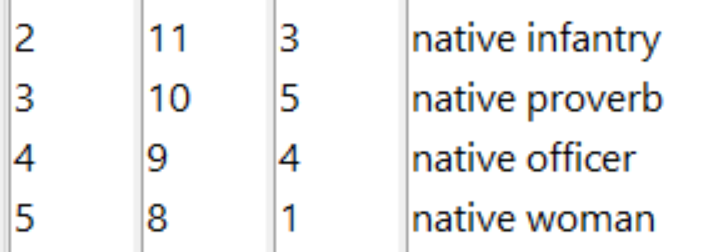

Clusters related to "black", "white", and "native"

Running the cluster tool on these words backs up our hypothesis: in the most frequent clusters containing them they are used as adjectives to describe skin colour or origin.

4. babu

14. brahmo

38. rani

Keyword rankings for Tagore social descriptors.

In Tagore, on the other hand, these descriptors are rarely used. This could mean that, in his work, society is divided in a different way. Running the keywords tool on Tagore’s works gives us a completely different classification of society: showing us titles that denote distinctions within what in Kipling is just “the natives”: “babu” (#4), “brahmo” (#14), and “rani” (#38) appear along the character names in the top of the list of keywords, which bears barely any mention of adjectives for the distinct ethnic groups of India.

Concluding thoughts

This exercise let me see what word frequencies can tell us about the assumptions and the cultural context behind a text. Also, analysing these frequencies can be used to obtain a fairly accurate estimate of the “what?” and the “who?” of large volumes of text. For example, we just discussed the distribution of main characters throughout the corpus, how they are described, and attempted to relate their characteristics to the individual contexts of the two authors. However, the “why?” remains slightly unclear with this kind of distant reading: is encountering different distributions of racially-charged words a sign of a hidden intent by the author? Or is it a reflection of their context? Or, more interestingly, have I, knowing that Kipling’s postcolonial reception has been less than favourable, unknowingly directed my interpretation of these word-lists towards something that confirms my own preconceptions?

This exercise has made me notice that computer readings can be far from objective, and it takes much more than automating one part of the process to get rid of bias. But, in the end, do we really want to get rid of it?

ready for grading - september 21st, 2021